|

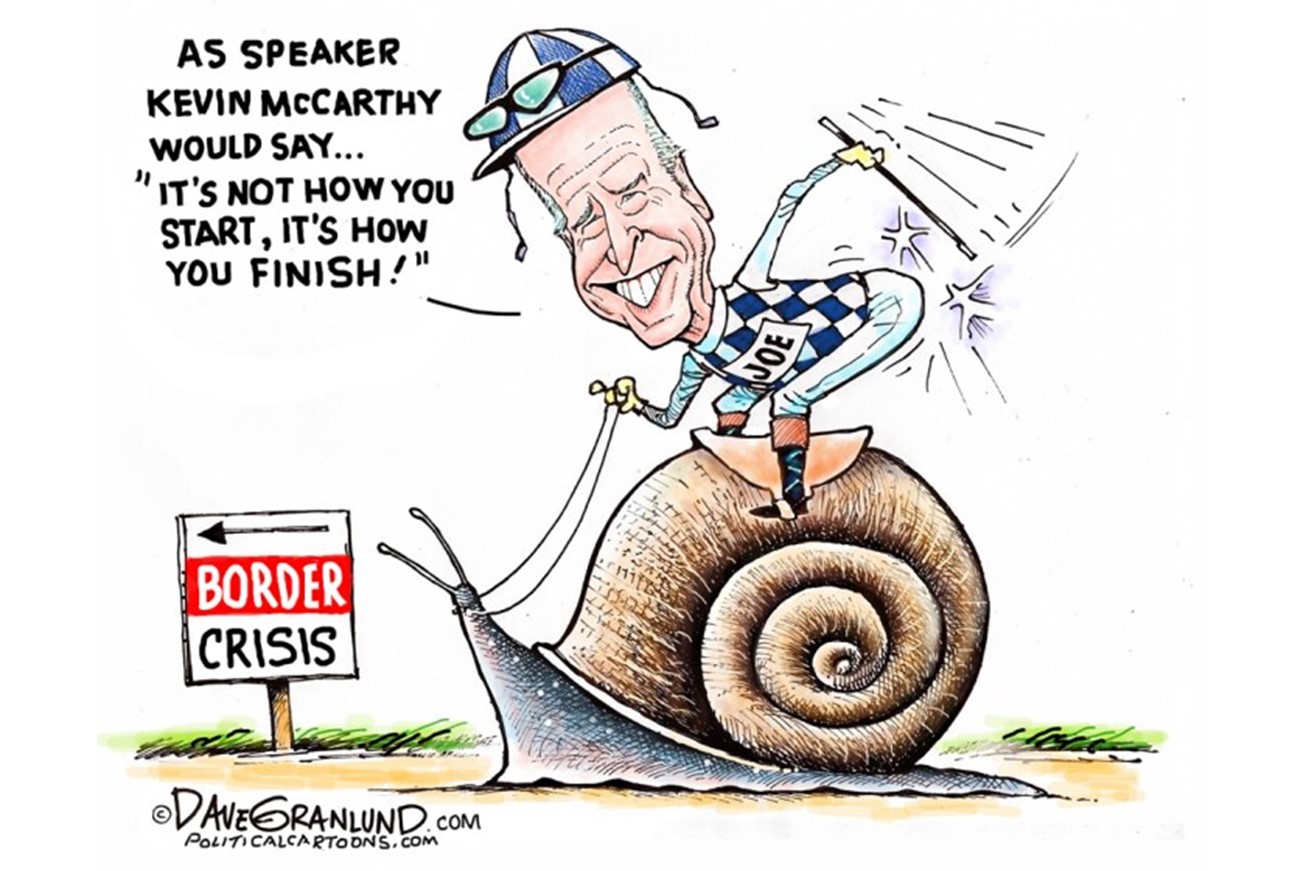

Local View: Politics, not principles, driving who gets into the US |

|

From the column: "What amazes me most is the rhetoric used to describe humans who want to come here."

By John Freivalds

Published 1/14/2023.

Duluth News Tribune

Ever wonder when the dehumanizing rhetoric of Latin-Americans migrants began? No, it wasn’t with President Donald Trump. It started in 1965 when a new system of immigration control was introduced. The old system had built-in bias against Catholics and Jews, and the Center of Immigration Studies concluded that “the new system is widely credited with having spiked a shift in the composition of immigration away from Europe (and) toward Latin America.”

I lucked out because I got into the U.S. under the old rules. Plus, the U.S. ended a legal way for Mexicans to enter the U.S. called the Bracero Program, which gave work permits to Mexicans.

Goodness, growing up I remember the bad jokes about the few Mexicans who swam across the Rio Grande, earning them the insult of “wetbacks.” All they did was take “siestas,” proclaimed the ignorant. The new rules meant that unauthorized immigrants rose from near zero in 1965 to more than 10 million now. The center points out: “How this happened is a complicated series of unintended consequences, political opportunism, bureaucratic entrepreneurship, media guile and most likely a healthy dose of racial and ethnic prejudice. “

OK, politics takes over, and common sense is thrown away.

The political opportunism was the stepchild of one Patrick Buchanan, who ran for president in the 1990s. He recognized that immigration was a good political issue to run on — and, boy, did he run with it. Prior to 1965, there were almost no negative metaphors describing Mexican immigrants, save “wetbacks.” We had marine metaphors like “rising tide” or the “tidal wave” or “flood” of immigrants. However, this soon gave way to martial metaphors like “alien invaders,” “invasion,” or even “Bonzi suicidal attacks.” Former President Trump added to this dehumanizing rhetoric by stating that, “Mexicans are bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

President Ronald Reagan even said that illegal immigration was a question of national security. In 1986, he told Americans that “terrorists and subversives are just two days driving time from Harlingen, Texas.”

Patrick Buchanan outdid Reagan by a mile. He said illegal immigration was “part of a plot hatched by Mexicans to recapture land lost in 1848. And if we don’t get control of our border, I see the dissolution of the United States (and) the loss of the American Southwest.” Buchanan finished by stating, “More Mexicans entails the end of a sovereign, self-sufficient, independent republic, the passing away of the American nation. They are coming to conquer us.”

Yikes! What amazes me most is the rhetoric used to describe humans who want to come here. It takes three terms to describe me: a “refugee” who escaped communism, a “displaced person” who spent five years in a displaced-persons camp in Austria, and an “immigrant” who came to the U.S. legally. And when I sponsored a Cuban family of five to settle in Minnesota, I got applause for helping Cuban “exiles.”

Some terms just apply to certain groups. For example, you have Cuban exiles but never Cuban aliens. Mexicans are never referred to as refugees, as authorities are wary of using that term for it implies we must let them in and give them asylum. Thus, no problem with Ukrainians being called refugees — but not Haitians. It suits some people to call Mexicans “illegal immigrants,” because it associates them with criminal behavior, as Don Flynn of the Migrant Rights Network has stated.

Did you get all that?

Immigrants will continue to come regardless of what we call them or how many walls we build. There is no hope in the country they are leaving, and there is hope once you get to the U.S. People don’t stop buying lottery tickets even though the chances of winning the big one are slim at best. Undocumented immigrants and lottery players are looking for the same thing: hope.

John Freivalds of Wayzata, Minnesota, is the author of six books, is the honorary consul of Latvia in Minnesota, and is a regular contributor to the News Tribune Opinion page. His website is jfapress.com.