Latvia’s linguistic journey |

|

By John Freivalds

Published October 24, 2019

Multilingual Magazine

Tourism is popular the world over, as MultiLingual’s new issue on tourism can attest to. And Latvia is no exception.

Once, at a resort in Whistler, British Columbia, I was surprised to meet a trainer with AirBaltic, the flag-carrying airline of Latvia. The trainer told me that when AirBaltic started flying in 1995, its flight attendants only knew Latvian and Russian. This was unfortunate when it started expanding its route system throughout Europe. Additionally, the seat-back pocket safety instruction was in Latvian and Cyrillic Russian, which did little good for a Frenchman traveling to Latvia for the first time.

“To survive, Latvia had to become more than a bilingual society,” the trainer told me. Before Latvia’s independence in the early 1990s, you needed Russian to get ahead — and aside from Latvian-Russian schools, all other bilingual schools were shut down under the Soviet regime. But after independence, English became the second language in Latvia, especially for the younger generation. And then Latvia joined the EU, and with the adoption of the euro it could attract tourists from all over.

The translation issue to promote tourism became apparent during my first trip back to Latvia in 1989. There were no translation companies and most translation was done by Baltic speakers in their countries. I know — I translated the franchise agreements for Coca Cola and others into Latvian while living in the US.

The OECD now reports that tourism is booming in Latvia. In 2012, for example, “The top source markets for international tourist arrivals were the Russian Federation, Lithuania, Sweden, Germany, Estonia and Finland, together generating nearly 70% of the total overnight count.”

Latvia finally realized that tourism means economic development, and a Latvian tourist development agency was formed in 1997. The tourism campaign came up with the recent slogan “Explore Latvia slowly,” focusing on road trips. I like this slogan better than that of neighboring Vilnius, Lithuania: “Nobody knows where it is, but when you find it, it’s amazing.” You can use your imagination as to what this latter slogan is referencing, or you could watch the John Oliver clip about it.

My two favorite places in Riga, Latvia, are the Riga Central Market and the Occupation Museum. The Occupation Museum shows what happened to Latvia during two totalitarian regimes: Nazi Germany and then the USSR. Its mission, explained in Latvian, English, Russian and German, “is to remember those who perished, were forcefully deported, or fled the terror of the occupation regime.”

My two favorite places in Riga, Latvia, are the Riga Central Market and the Occupation Museum. The Occupation Museum shows what happened to Latvia during two totalitarian regimes: Nazi Germany and then the USSR. Its mission, explained in Latvian, English, Russian and German, “is to remember those who perished, were forcefully deported, or fled the terror of the occupation regime.”

Today, translations are everywhere in Latvia. To attract foreign investment, the Latvia development agency where I served as the US representative for 16 years has a website (www.liaa.gov.lv) in Latvian, English, Russian, Japanese and Chinese. Russian firms are coming to Latvia, and perhaps the most notable is Stolichnaya Vodka (Stoli), which now makes much of its vodka in Latvia.

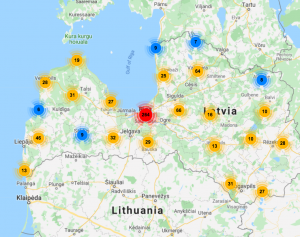

To deal with some of the issues that researchers found in foreign language availability, the Latvian government set up a travel portal that provides maps and booklets in a variety of languages for each of the four regions of Latvia. This is pretty amazing given that Latvia is not a huge country — and the documents are localized for different demographics. For example, Booklet about Latvia is in Korean and Chinese, and Cycling Routes in Latvia is in Latvian, English, German, Russian and Dutch.

John Freivalds runs an international communications firm and is the Honorary Consul for Latvia in the US State of Minnesota.

John Freivalds runs an international communications firm and is the Honorary Consul for Latvia in the US State of Minnesota.